Sublime Text has a handy feature called “Minimap” which shows a small condensed version of your text file along the right hand margin. This gives you a high level view of the file you’re working in and what the file looks like if zoomed out so far that you could see all the text on one screen. This can help in navigating around very large files. I took some inspiration from this feature, thinking that if it can be useful for text files, it may also be useful for datasets! I’m writing an R package for exploratory data analysis in the browser with React and the Minimap is the first feature that I’d like to showcase to demonstrate what’s possible by leveraging a front-end web application to power data analysis. Please read A Front-end for EDA for a more detailed introduction to this project.

A common problem when working with data is trying to understand the big picture from the very small sliver that you can view on your screen at any given time. Imagine your dataset as a text file that we can zoom out to a high level just like Sublime’s Minimap. By placing each variable’s distribution side by side, you can understand a lot about the data that otherwise you may not be able to see without plotting or summarizing each variable separately.

Let’s see what we can learn with this kind of visualization. Please

note that this is a very early prototype and there are a lot of

improvements and tweaks necessary before these minimaps will be good

enough to release. First, let’s look at a dataset that should be very

familiar to R programmers, mtcars:

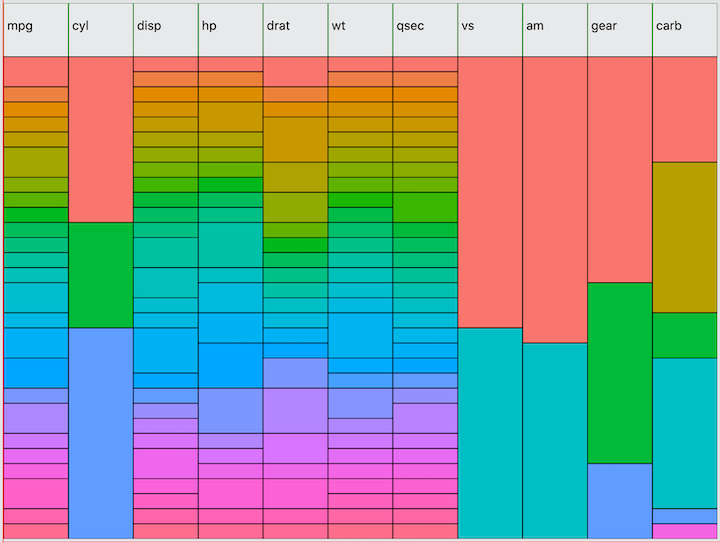

I am using the same method for selecting colors as used in ggolot2 to

visually distinguish each value of each variable independently. This

allows you to quickly see the distribution of each variable. One feature

not shown here is a tooltip that will render when hovering over the

minimap containing the variable name, value, count, and percent of total

observations. For example, hovering over the first value of

cyl would tell you that the value is 4 and the count is 11

observations, representing 34% of the total.

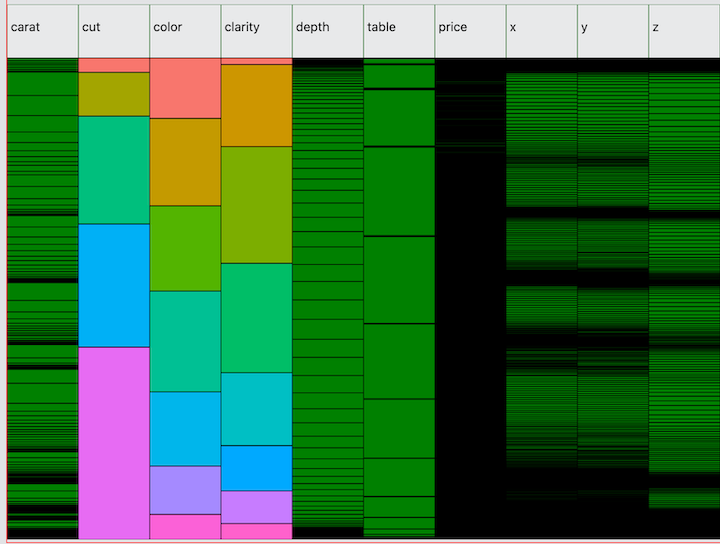

Next, here is the diamonds dataset from ggplot2. Unlike mtcars, this

dataset has several high cardinality variables—caret,

price, x, y, and z.

Note the normal distribution of depth. Compare this to

ggplot(diamonds, aes(x=depth)) + geom_density().

In the minimap, you basically get a “top-down” view of the density

function.

Also notice that there are several interesting values of

price where you can see green cells peeking through the

black borders. From this we can see that there are a few values at which

multiple observations are concentrated in what is a high cardinality

variable without many repeated values. To discover this in R, you could

run ggplot(diamonds, aes(x=price)) + stat_ecdf()

and look for the tiny bumps in the cumulative distribution function

where the y-values flatline. But typically it is not easy to detect

anomalies in high cardinality variables. The Minimap visualization is

still very crude for such variables. Still, it is surprisingly easy to

find strange values and in testing I was able to locate a strange clump

of values in a dataset that I later tracked down to a formula error in

the source csv file!

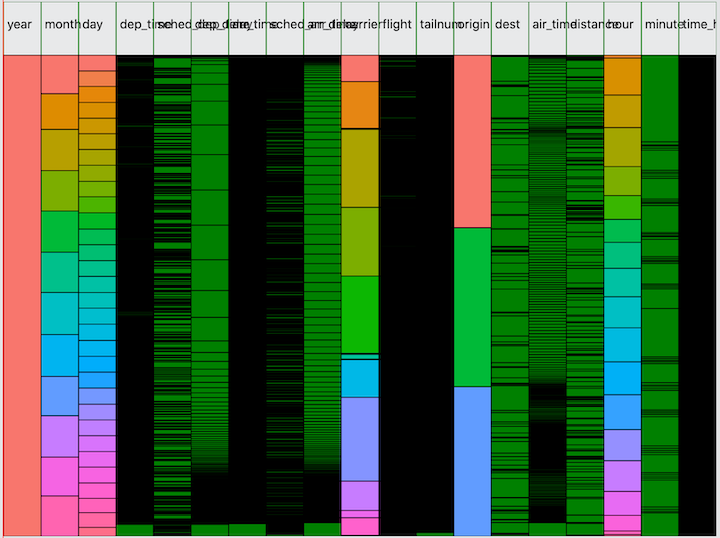

Let’s look at one more dataset: flights from the nycflights13 dataset. The column headers still need a lot of work!

Now I ask you, how long would it take to give you this level of

visibility from a) printing the dataframe, b) running

summarize or count on each variable, and c)

finding a decent plot that works for each variable? I’m not going to

argue that the Minimap is a magic bullet—just like Sublime’s Minimap

won’t magically give you all the insight you need to refactor your code.

But it’s a useful tool in the toolkit combining in one visualization

what would otherwise require running through several different pieces of

output.

How these work

The minimaps are made from SVG rect

elements rendered by a React application served by the Fiery

package in R. When the React application is launched in the browser,

Fiery will listen for web requests from the front-end which enables R to

run some functions and return data to the browser as json. One of these

functions I’ve written will tabulate all the variables in a dataframe,

returning the values and counts of each variable as an array called

vartabs as in the following example for mtcars:

{

"vartabs": [

{

"name": "cyl",

"value": [

{

"cyl": 4,

"n": 11

},

{

"cyl": 6,

"n": 7

},

{

"cyl": 8,

"n": 14

}]

}],

}My Minimap is a React component that I call with the following props:

<Minimap vartabs={props.vartabs} varcolors={props.colors} n={props.n} />The varcolors prop is an array of the same dimensions as

vartabs, containing the color chosen from a color palette.

The Minimap component loops over the vartabs array to

generate the rect elements for each variable name as column

headers and then calls a VariableRect component to handle

each variable individually. Leaving aside the code for managing the

tooltip that runs on mouse hover events, the Minimap component looks

like this:

function Minimap(props) {

const { vartabs, varcolors, n } = props;

if (!vartabs || !n) {

return "Loading Minimap...";

}

// TODO: dynamically size the map based on number of variables!

const mapWidth = 800;

const mapHeight = 600;

// create rect elements for column headers

const colHeaders = vartabs.map((v, i) => {

return (

<Fragment key={v.name}>

<rect

key={v.name}

x={i*mapWidth / vartabs.length}

y="0"

width={mapWidth / vartabs.length}

height="60"

stroke="green"

fill="white"

fillOpacity="0.2"

>

</rect>

<text x={4 + i*mapWidth / vartabs.length} y="30">{v.name}</text>

</Fragment>

);

});

// create rect elements for the values of each variable

const cells = vartabs.map((v, i) => {

const x = i*mapWidth / vartabs.length;

const fillColors = varcolors[i].value;

return (

<VariableRect

key={v.name}

vartab={v}

x={x}

varWidth={mapWidth / vartabs.length}

n={n}

varHeight={mapHeight}

fillColors={fillColors}

/>

);

});

return (

<div className="minimap">

<h3>I am a minimap!</h3>

<svg width={mapWidth} height={mapHeight}>

<g>

{colHeaders}

{cells}

</g>

</svg>

</div>

);

}The VariableRect component’s job is to loop through each

value of the variable, determining the appropriate height based on the

count of values.

function VariableRect(props) {

let prevHeight = 60; // fixed height for column headers

let y = 0;

return (

<Fragment key={props.vartab.name}>

{props.vartab.value.map((cell, rownum) => {

y += prevHeight;

const h = cell.n / props.n * (props.varHeight - 60);

prevHeight = h;

return (

<CellRect

key={`cell_${rownum}`}

cell={cell}

n={props.n}

varname={props.vartab.name}

rownum={rownum}

x={props.x}

y={y}

width={props.varWidth}

height={h}

fillColors={props.fillColors}

/>

);

}

)}

</Fragment>

);

}The basic implementation of the CellRect component is

quite simple, since all the dimensions have already been calculated. The

reason for making it its own component is because I’m also using it with

event handlers to enable the tooltip (removed for brevity!).

function CellRect(props) {

const fillColor = props.fillColors[props.rownum] || 'green';

return (

<rect

key={`cell_${props.rownum}`}

x={props.x}

y={props.y}

width={props.width}

height={props.height}

stroke="black"

fill={fillColor}

fillOpacity="1.0"

>

</rect>

);

}Reproduction in ggplot2

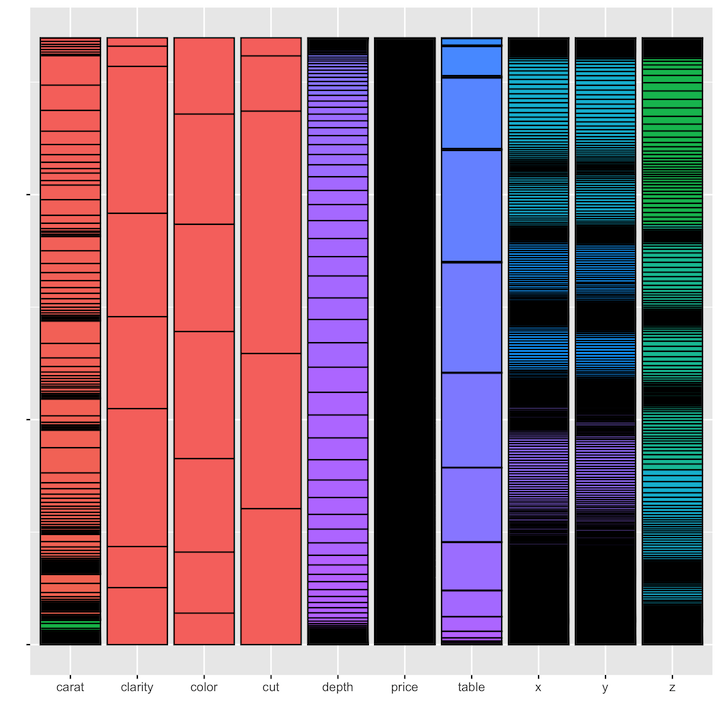

Is it possible to reproduce these minimaps in R? With ggplot, anything is possible! One approach is to map each variable to the count function and aggregate all the values back into a single dataset:

diamonds %>%

map(~count(tibble(x=as.character(.x)), x)) %>%

enframe() %>%

unnest(cols = c(value)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = name, y = n, fill = x)) +

geom_bar(stat="identity", colour="black") +

theme(legend.position = "none", axis.text.y=element_blank()) +

labs(x = "", y = "")As you can see from the results, there are a few issues. First, we’ve

had to reduce all variables to the lowest common denominator of

variable type, in this case using as.character because all

of the values across all of the variables in the dastaset need to be

represented as the same type. A second issue is that with all of the

values combined, the color palette assigns colors based on the full set

of values, rather than re-assigning colors independently for each

variable. This reduces the amount of visual discrimination in the

display of the fill colors.

In addition, we cannot use this method to display the variables in

dataset order. Instead they will be displayed in alphabetical order

based on name. The only way to bypass this would be to hard-code the

desired order of the variables in the levels of a factor: aes(x=factor(caret, cut, color, ....

Another solution is to use faceting, but again the same issues arise—the values of all the variables will need to be aggregated together into one variable in order to use that variable in a facet. The only way I’ve found to avoid this is to simply plot each variable independently, and then find a way to pop them all onto the screen at the same time.

The Wrap-up

The current prototype still needs a lot of work. In addition to

fixing the printing of column headers and making the map dimensions

flexible based on the number of variables, there’s also a performance

issue with large datasets (when isn’t that the case?). The

flights dataset with 336k rows and a lot of high

cardinality variables means I’m drawing several million

rect elements in the svg. That means several million event

handlers for the mouse hover tooltip, which causes a nearly unusable

lag. Fixing this will involve separating out a

HighCardinality component where we limit the number of

rects we will draw to something more manageable. But I still want to be

able to display the useful information, notably the presence of any

“clumps”. The approach I’m taking is to draw the top N values and fill

in the gaps with gradients.

I would also like to add a zoom feature, which svg makes possible–it is ‘scalable’ after all! You could even imagine being able to gradually zoom in to a point at which you’d be able to see the values of individual rows, as if it were just a table. This might not be necessary, however, because of course I’m also displaying a data table component so the Minimap doesn’t really need to serve this purpose. Still, zooming would still be useful to increase the resolution for those tricky high cardinality variables.